TL;DR

Caching in microservices can help with improving performance and scaling if used wisely. Opt for service level domain aggregate caches and use mashed up object caching on client services only when you are trying to speed-up/avoid local processing on remote data. Don't use blackboard caches and remember cache cannot be a source of truth or a permanent data store.

Origin Note

This article is based on a talk I gave at an event hosted by Everest Engineering. The article serves both as a independent reference on the topic for anybody and a refresher for people who attended the talk.

Why caching in Microservices

Microservices offer us a lot of advantages but they are not a silver bullet. Every architecture tries to satisfy the “ities” . This architecture style is no different. It is very promising but it is not without its trade-offs.

Everyone has heard of caching. It is prevalent in our world of computers and software at multiple levels. From the CPU level L1/L2 cache, to in-memory caches in our monoliths, all of us would have seen caching in some place or the other. Why is it used? There are two desirable characteristics for any user feature:

- Respond to the user very fast - performance.

- Respond to a lot of users - scale.

And caching can help with both.

But do microservices need them? Microservices already offer a lot of good qualities to our systems - like independent scaling, independent data storage for better performance etc. . So should we care about caching. Also caching is not the easiest thing. You might have read about the saying in Martin Fowler's bliki - Two Hard Things:

There are only two hard things in Computer Science: cache invalidation and naming things

To answer this let us dig deeper to identify challenges which microservices introduces.

Use case - Viewing/Editing an online document

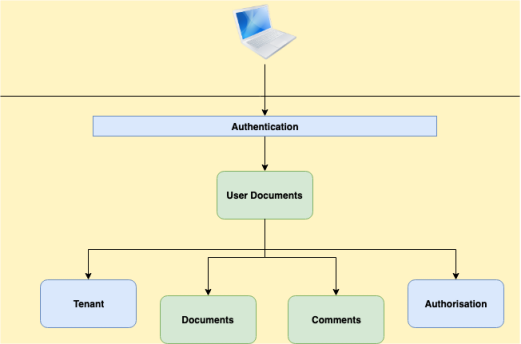

The use case is pretty common. So let us look at potential architecture for making this work. For showing a single document to the end user there are 5 - 6 services involved if we adopt microservices architecture.

The individual components are:

- Document service - This one serves the original document.

- Comments service - This one provides the various comments created on top of the document by different users.

- Authentication service - This is a system service which ensures that the call to the document service is from an authenticated user. This could be API gateway but I am representing it as a service so that it is clear that it is another layer/system involved in the interaction.

- Authorisation service - It checks if the user can see/edit the document - Action level authorisation.

- Tenant service - This ensures that the document requested belongs to the same tenant as the user - Data level authorisation

- User Document service - The Orchestrator. This talks to the underlying services and mashes up the final information and sends to the user.

Given the above architecture, let us think about performance. Generally a single request made by the user is expected to respond within 300-500 ms. The idea is that if the first byte comes through fast then, there is some time for the browser to visually display the content along with any client side processing it has to do within 2-3 secs.

In the above microservices architecture instead of one service (monolith) returning within that time, all these 5 services should work together to respond within the same time. For simplicity, if we are thinking of splitting it up equally we are talking about 50-80 ms per service. That can be pretty tight. If the page is not ready for end user consumption in 2 - 3 seconds, the user will move to a different document editor provider.

Microservices offer a lot of good. But in this context where we need great performance, the need to talk to multiple services to respond to one use case can mean a very slow and painful experience for the end user. Not good. We need to do something. What can we do which will help us improve performance and scale? Caching!! Applying caching to microservices allows us to hit our required goals. That does not mean that we apply caching to anything & everything. There are things to consider, things to manage.

Now that we have established why caching is useful, let us get into more detail about caching. Let us start with what you would want to cache.

What to cache

A general cache acts like a map or hash or dict. Pick your term based on your language of choice. Any object is added to the cache by identifying it with a key. A cache generally does not care what value it caches. You can then retrieve the value using the key. So we could cache any kind of object in a cache. But what should we cache?

Out of scope

Before we go deeper, I am not covering the entire topic of http caching. While http caching is useful in the context of microservices they are not really specific to them. It is applicable more generally.

Domain objects/aggregates

In the world of services (I will interchangeably use service and microservice because I believe microservice is just a SOA service done right), one of the primary things you should consider caching are domain aggregates or objects. Any given microservice generally deals with one primary domain aggregate or object (may be two if it makes sense). In the example we talked about earlier, we had an comment service whose primary domain object is comment. Similarly document could be the one for document service. Caching the primary domain aggregate/object means that all relevant information required by the client can be easily served up quicky without looking at multiple places - especially the database. The actual response could be a subset of the data, but caching the aggregate allows us to adapt & support many use cases. We know databases and associated disk reads can be the cause of big performance delays. By caching domain aggregates we make it much easier for the service to serve its clients. There are still things to consider here. We will discuss about it down the line.

Configurations

Another thing we look at caching is configurations of a service. This one is fairly common even in the monolith world. Configurations generally don’t change much and are used in different parts of the app - hence they are a great candidate for caching.

Mashed up objects with processing/calculations

The above two cases are straight-forward. Next thing to consider for caching is mashed up objects. This is typically employed by an orchestration service acting as client to other services, and it involves merging in responses from these services, doing some calculations or processing on top of them and caching the result. Again referring to the use case above, the user document service might take the document(s) from the document service and merge the applicable comments from comments service and cache these rich documents on its side. This means that you not only avoid round trips to other services but also don’t need to do the additional processing to match, merge and position them. This means better performance and also lesser load (hence better scale) for all the services involved. There are trade-offs involved here too and we will get to them.

As a general advice, I would say that you should cache everything BUT only if you can.

Where to cache

Now that we know what to cache, let us talk about where to cache.

In service memory

Within a service, we could just use an in process / in memory cache and improve performance with great ease. This works, but is applicable for a very limited set of use cases. One example is static configuration information. This is not very large in size can be stored in a in-memory, in-process cache. Given that any service worth its salt will be setup as a cluster in a production setup, we have a replicated cache in each of the service nodes. This cache will be the fastest of all since it is not just in memory, it is in same process as the service.

The above approach allows us to get started, but falls apart soon. When we want to cache domain aggregates/objects, a clustered service will find it very difficult to keep changes in sync across the memories of multiple service nodes. Also, once you go down the path of caching and get the taste of performance gains, you will plan to cache a more in memory. This means that the cache is competing for memory with the actual service procesing requests. This can lead to reduction of service scale. It is time to move out of service memory.

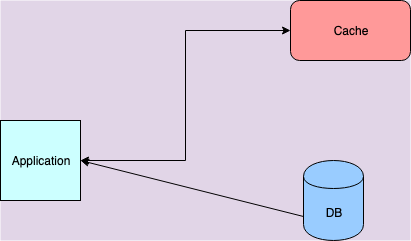

Out of service memory - Standalone

The first obvious choice here is to have a standalone caching solution which can be reached by different service nodes for both reading and writing data. This is obviously going to be slower than the in-process cache but it will still be faster than going to the database and doing disk reads. Also given that it is separated from individual service nodes it removes the overhead created by cache storage on the individual nodes. Typical solutions used here are Redis, Memcached etc.

Out of service memory - Distributed

When we want scale these even further, we get into distributed caching and in-memory data grids. These solutions allow for multiple nodes holding a large amount of data in memory for faster response and higher scale. It is not uncommon to have a 100 node cluster of in-memory data grid machines which are hosting terabytes of data in memory by employing partitioning of data across different nodes.

Each of these individual solutions provide a lot of different features but that is not our focus.

What we have covered now is a broad base of locations where data could be cached. Each location of storage has pros and cons and are suited depending on our needs.

When to cache

We now know what to cache and where to cache it. Now let us discuss when we would cache any data.

On Demand

One approach to populate the cache with data is when it is required. When a particular piece of data is requested and the cache does not have the same, then the data is picked up from the source, the cache seeded with the same and then returned back to the requester. This is the On Demand mode of populating a cache. This mode can work in most scenarios but has a couple of drawbacks. The first request which populates the cache will be very slow and leads to a bad experience to that end user(s). The other one that if there are multiple service nodes which request for the same entry then it could cause database contention.

Pre-loading

The other approach to when to cache is to pre-load data upfront. As part of the service initialisation process, the cache was seeded with required data. This means that there is a huge load on the data store during start up and hence a potential delay in start up. But once the loading is complete, the cache is primed and end user experience is great - no more delays even for the first user. And if you cache most of the relevant data, we might even survive a db outage! One problem with this is that, we don’t know what to cache if we are not planning to cache everything.

How to cache - Patterns

Let us get into details of how caching can be implemented within microservices. There are some well known patterns for reading and writing to cache. These have their pros and cons as well. Also they are not mutually exclusive in any way. They generally work together to solve problems. Let us go through them one by one.

Cache aside

The first one is the Cache aside pattern. This is the most common pattern and used extensively. The idea of the pattern is to treat cache as a different store similar to the database. A service would read and write to the database and the cache as an aside. The control of what and when data are written into or read from the cache lies with the service itself. This pattern is great for read heavy workloads. Also we could write the service in such a way that during a failure in cache setup - when we use standalone/grid mode - the service can still keep serving from db. Of course this can’t be sustained for long given the cache setup is to support scale, but the option is there. The approach for when writes happen depends on us. Writing to database is the first thing the service will do - almost always. What happens to the cached entry is subject to developers choice - the patterns leaves this open to us. One thing to do is to just remove or invalidate the entry from the cache. There are others options available.

I prefer this approach because as a business service writer I have lot more control with this approach. Hence I have used it a lot as well.

Sometimes we really don’t want so much control. Rather we want convenience and ease of use. The following patterns afford this one way or other and the unifying aspect of these patterns is that the caching library or system acts as the facade and controls how data is written/read to/from the underlying source data store.

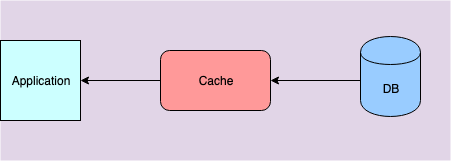

Read through

The first one among them is the Read-Through pattern. Here the cache, when requested for a entry and not finding it, will initiate a call to the underlying store to read the data. It will then cache it and return the data to requester. The key thing to note here is, the cache is the one orchestrating the action. This is different from how cache aside pattern works where the control is with the service code. Also Read through pattern follows lazy or on-demand loading and hence has the same caveats. We must also remember that in this pattern the data structure cached must match with the structure stored in the underlying store.

Even in Cache aside, we could follow a similar technique of lazy loading when writes happen (i.e writes just invalidates the corresponding entry in cache if it exists) if the applicable caveats work for you.

Write Through

The Write Through pattern is about writing data. This is similar to Read-Through - the cache system sits in between the service code and database. With this approach when changes are made to the cached entity, the service writes into the cache and that in turn writes into the database. Both writes need to be completed before completion of request. This adds a bit of an overhead to the write operation but when combined with Read Through pattern it gives a lot of benefits. The write through pattern ensures that entries in the cache are not out-dated or stale. So we have consistent data available at very high speeds for reads. This is great for a cache.

Even with the Cache Aside pattern, we generally employ a similar approach to read through and write through. The difference is of course that the service controls the entire interaction rather the cache system.

Write-Around

Write-Around Cache is a slightly different from the older one. Here the write happens only to the database and the cache is updated only during a read through. There are some advantages - writes are faster but at the same time they are durable (since db is written). But reads could miss cache or even return stale data. This approach is great for write heavy workloads where reads are much less - e.g. is real time logs.

Write-Back or Write-Behind

Write-Back or Write-Behind Cache is another variation. Here the service writes to the cache and returns. The cache will write to the DB behind the scenes with some potential delay. Of course writes are super-fast but there are chances of missed writes too. Combined with read through, you get a good cache times for most mixed workloads - you always have the recently updated and accessed data. Also one can argue that it is resilient to db failures - (but how long? - keep that in mind). Another thing possible is that multiple writes to the same object could be coalesced into one write to the db.

As I said earlier these are general patterns which have trade-offs. And they are always combined. In my own opinion, treating a cache as a data source is rarely a good idea. Unless you have throwaway data or what you holding is always derived reconstructable data. If not stick to the more durable write patterns always.

How Long to Cache - Invalidation

We are now embarking on the one of toughest problems in computer science! (referred already). In my experience this is a true statement.

Any cache we create is an alternate store of data and cache is not the source. That means it is bound to go out of sync with the source. This is called as going stale. Unlike stale food, stale data from cache is not always bad. That said we can’t keep having stale data and serve our clients with the same. How long we can use stale data depends on your business scenario.

News sites with stories could show some stale data - slightly older news - may be few hours. But a stock ticker like app which enables users to trade cannot real work with stale data! So it depends.

Let us figure out how to get out of this stale state.

Expiry

One of the ways to deal with staleness is expiry. Depending on the data you are trying to cache, you generally know how long the data can remain fresh and live. If so, we can set the data to expire. This is generally called Time To Live or ttl. Most caching frameworks will drop the data once it passes ttl - either actively or passively. A request for this expired data will result in a cache miss. The next step depends on the caching patterns you use. Many caching frameworks allow us to set this expiry at the bucket level (all new stories) as well as individual item (a particular new story) level - we can use any as required.

Service based

While expiration is a reasonable way of handling invalidation, we could handle it more actively. When we use caching within a service boundary, a service has control over the data which it is caching and hence can actively manage the invalidation of stale data. For example when more comments are added to a document, the change happens through the service and it can actively manage the cache invalidation. This is one of the reasons I prefer the service based approach.

Events based

Another way invalidation can be achieved is through events. This technique is especially applicable when orchestration service clients cache mashed up data. When the object owner service finds that data has changed, it sends out an event to an event bus or MOM. This is consumed by the orchestration service to take appropriate action.

Two more concepts on Caching

Measurements

Anything we do, we should measure. There is a saying in Tamil

ஆற்றில் போட்டாலும் அளந்து போடு

Even when you are just going to throw something into the river you should measure and throw it.

One of the critical measurements for any caching setup is the cache hit ratio. Every one understands what a cache hit is - when a cache access succeeds. And a cache miss when you miss. So cache hit ratio is:

Cache Hit Ratio = Cache Hit / (Cache Hit + Cache Miss)

For caching to be considered effective, the data cached must have a good cache hit ratio. If you have a low cache hit ratio then you are surely doing something wrong. Either you are using the wrong cache patterns or you are caching the wrong data. Any changes you want to do related to caching (change methods/techniques or something else) must keep the cache hit ratio in mind. Any change reducing the cache hit ratio is a bad idea.

Eviction

We talked about expiry a lot. There is another concept which people consider closely related to it - Eviction. Actually eviction is very different from Expiry. It has more connection to the cache hit ratio and what to cache question. Both expiry and eviction deal with removal of entries, but their causes and purposes are completely different.

Cache eviction comes into play because memory is a finite resource - for the most part that is. While I would love to cache the entire database it is just not economical to do it. So once the amount we cache exceeds a number limit or memory limit, any addition of entry means some other entry needs to be removed out of memory. This process is called eviction. Eviction is generally done based on some algorithmic strategy. Different caching frameworks provide many different algorithms. The most common ones are LRU, LFU, FIFO.

LRU is the most common is generally considered a reasonable default. It is considered a close proxy to the most optimal caching algorithm. The specific reason is due to Locality of reference. This is easily explained in the context of caching at the CPU level where the recently used data or instruction is repeatedly requested by the CPU. This is called Temporal Locality. The same phenomenon applies to the real world usage of cached data too. We can understand this intuitively. For example most times when data is created it is immediately accessed. Also when real users surf through data like products they tend to return to see the same products again and again. Another example is generally items like dresses or vehicles come into trend in time cycles (or may be because there is a big sale going on). Temporal locality makes sense. In my experience of using caches, I have never needed to change the eviction algorithm to something else. Nor have I heard of any real life usage of any other algorithm - that is anecdotal for sure but I am pretty convinced.

Changing a caching algorithm to something else is mostly a configuration change. The more important thing is, when we make such a change, we need to measure cache hit ratios and average response times and see how they are affected.

Conclusion - Summary of Opinions

Preferred Approach - Service Caching

I prefer to use service managed caches as an approach to caching. Given that service owns the data, as a service developer I have a much clearer understanding of how and when data changes and hence I can make decisions more easily. With this approach clients are unaware of what is happening and hence they are not affected by any changes to mode/mechanism of caching. I can keep tweaking the implementation as long as I satisfy the performance SLA. I can keep improving performance or scale without having clients to have to change anything. A service can internally use in process caching or stand alone caching to begin with and then move to an IMDG as it needs more scale. All good right!

But you sometimes need - Orchestrator/Client side caching

Not really. Service level caching does not solve all scenarios. Clients sometimes want even better response times than what service level caching can provide. Network latency could be one reason. I generally don’t really think it is a great argument since once you want to scale the client you would need an out of process cache and then the network latency is back. But that is not the only reason. There are situations where client services mash up data from multiple services and do some processing on top and use it. In such cases it might be required for that service to cache the outcome of the processing to quickly serve clients. I have done the same in one of previous situations because it was needed to meet the SLA for the service - to keep real users happy. Though this approach is sometimes required, we must understand that it is a complex thing to manage. We need to build in checks which will ensure that this cache data still ties back to original data source services - potentially an event based mechasim.

Never ever Shared Caches

One of ways which I have seen caching being used is like a blackboard where some service can write something and another service can read the same. This is possible to do but I am not in favour of it. This feels very much like multiple services using the same underlying database - a global namespace. Any change cannot be done in an isolated manner and every service can touch or be touched by all changes happening on the shared cache. So beware of it. I am not saying that this cannot be done. It feels more dirty and complicated and hence can turn ugly if we are not very careful.

And not really a replacement to DB

And last piece of advice or opinion. Never treat your cache as your database even if it super reliable with great clustering features. Some IMDG vendors say that it is possible. In my experience that is not what they are good at and hence they don’t work well as good persistent stores.

I am done. Share your thoughts or questions through comments below.

Starting Point

Starting Point

Comments

comments powered by Disqus